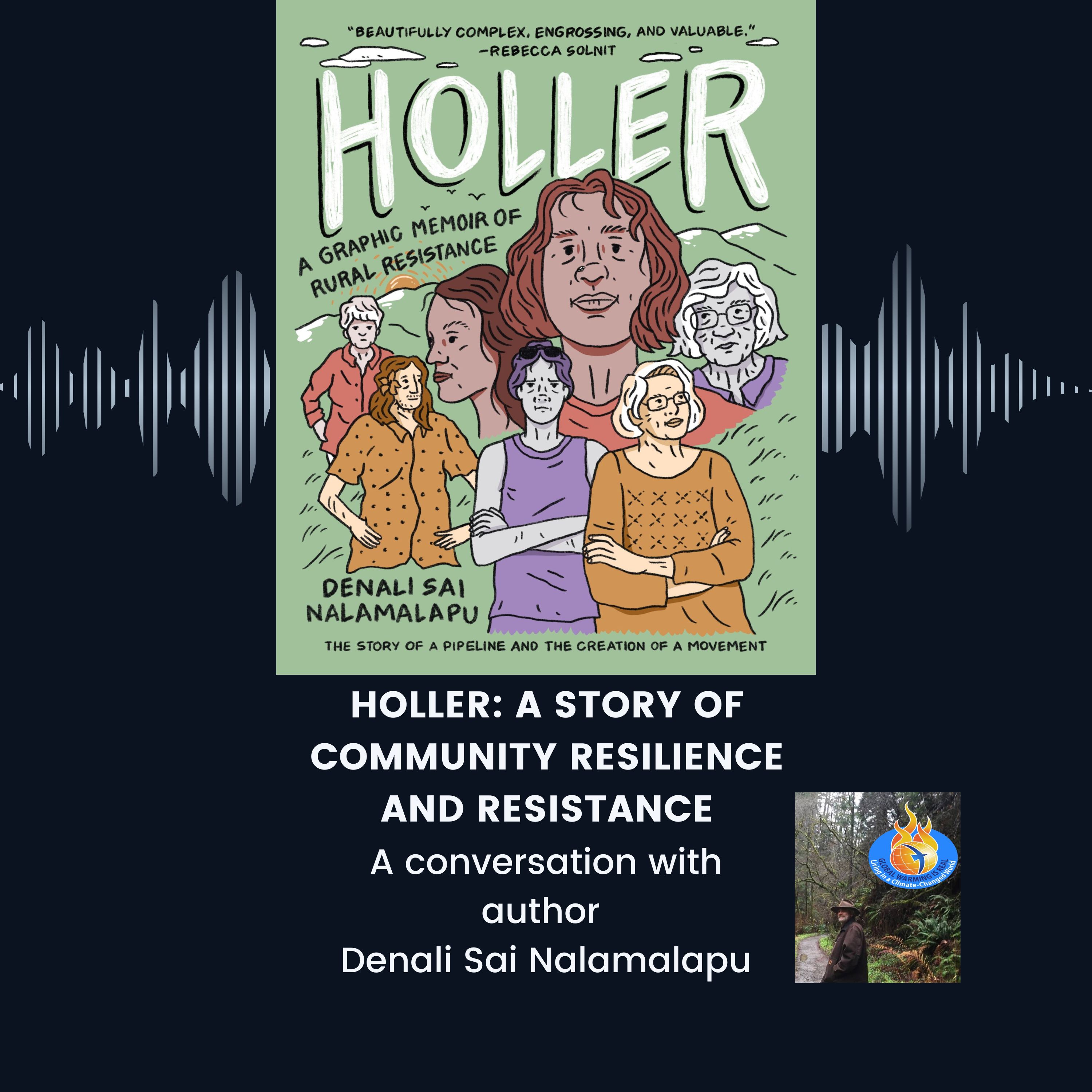

Hollar: A Graphic Memoir of Rural Resistance with Denali Sai Nalamalapu

The Mountain Valley Pipeline and Stories of Resistance in Appalachia

Amidst the Appalachian dawn, our exploration of community resilience and environmental justice unfolds through the lens of Denali Sai Nalamalapu, author of ‘Holler: A Graphic Memoir of Rural Resistance.’ The Mountain Valley Pipeline (MVP) stands as a stark reminder of the battles waged by local communities against encroaching corporate interests. Denali expertly articulates the complexities of this decade-long struggle, revealing how the MVP’s construction, initially presented as a critical energy project, has instead become a symbol of corporate overreach and environmental degradation.

The MVP was met with fierce and determined opposition from a diverse community of residents who understood the potential dangers it posed to their land, water supply, and way of life. We discuss the labyrinthine, back-slapping political maneuvering that allowed the MVP to be approved. A Faustian bargain at the highest levels, where environmental concerns and legitimate legal challenges were sidelined in favor of fossil fuel development–thanks to the intransigence of Senator Joe Manchin.

Denali shares her experience and the stories of others who have dedicated a decade or more of their lives to the fight, demonstrating that the struggle against the MVP was not just about preserving land or one pipeline, but also about asserting the rights of communities to defend their homes. The episode highlights how grassroots activism can mobilize resistance across diverse voices as a powerful force against exploitation.

The ongoing resistance against the expansion of the MVP into North Carolina serves as a testament to the indomitable spirit of those who refuse to back down in the face of corporate giants.

Denali’s insights remind us that while the battle may be tough, the path toward justice, environmental stewardship, and energy sanity is one worth pursuing. We can confront the Goliaths of our time, armed with resilience, community, and an unwavering commitment to justice.

Takeaways:

- The Mountain Valley Pipeline controversy underscores the conflict between local communities and corporate interests that prioritize profit over environmental well-being.

- Grassroots activism is not just a youthful endeavor; it encompasses voices from all ages, demonstrating the power of intergenerational solidarity in the pursuit of environmental justice.

- Despite the Mountain Valley Pipeline's construction, the ongoing resistance reflects a resilient community spirit that continues to challenge corporate exploitation of natural resources.

- Storytelling through graphic novels, as seen in Denali Sai Nalamalapu's work, is a compelling medium for conveying complex environmental issues to broader audiences.

- The fight against the Mountain Valley Pipeline underscores the importance of local knowledge and community connections in combating environmental injustices.

- Even in the face of setbacks, such as the pipeline's approval, the unity and determination of the Appalachian community serve as a beacon of hope for future climate action.

References:

- Denali Sai Nalamalapu

- Hollar: A Graphic Memoir of Rural Resistance

- Mountain Valley Pipeline

- MVP “Misleading and Disengenuous”

- Veterans fighting MVP

- GlobalWarmingIsReal

00:00 - Untitled

00:07 - A New Day in Appalachia

01:15 - The Struggle Against the Mountain Valley Pipeline

12:14 - The Intergenerational Fight Against the Mountain Valley Pipeline

17:24 - Building Community and Resistance

19:13 - Finding Activism in Community Engagement

30:58 - The Pipeline Controversy: A New Era of Environmental Concerns

34:58 - The Importance of Local Climate Action

38:35 - Mobilizing Local Action for Change

It's morning in Appalachia.

Speaker AYou rise to greet the day.

Speaker ALife out here is once spent next to the land, away from the noise and chaos of the busy world of striving and acquisition.

Speaker AOut beyond the fields, farms and meadows, the Appalachian Mountains reach up to greet the morning sun.

Speaker ATime for coffee.

Speaker AWater streams from the tap, the cull of a weak tea.

Speaker ADisturbing as that is, it's no surprise.

Speaker AIt's just another day in a land once relatively undisturbed until an energy hungry, profit seeking, frenetic world pressed in, taking, toppling, excavating, extracting.

Speaker AWhen in doubt, take the easy way.

Speaker BOut and build a pipeline.

Speaker AYou're reminded of the story of David and Goliath.

Speaker AYou didn't want to be David, just to be left alone to live on the land that you love.

Speaker ABut they're polluting the water, raising the landscape and claiming your neighbor's land.

Speaker AFarms that families have worked for generations in this episode of Global Warming is real.

Speaker AI talk with Denali Sai Nalamallapu, author of A Graphic memoir of Rural resistance about the 10 year struggle to stop the Mountain Valley Pipeline that involved Appalachians across age, race and background.

Speaker AContrary to the stereotypes of activism as solely a woke, whatever that means young persons endeavor.

Speaker AInitially proposed in 2014, the Mountain Valley Pipeline was promoted with scant supporting data as a critical energy project.

Speaker AIt wasn't.

Speaker AIt isn't.

Speaker AIt was one of the many disingenuous claims, AKA lies proffered by proponents of the boondoggle project.

Speaker AThe MVP soon met fierce resistance not just from environmentalists, but from multi generational, multiracial communities whose stories were rarely heard outside the region.

Speaker ASuddenly, these close knit, diverse and self reliant communities became the focal point of view the national reckoning over climate justice, political power and the future of America's energy landscape.

Speaker AFor nearly a decade, pipeline adversaries faced an uphill battle, navigating obscure corporate alliances, a regulatory system often tilted against them, and ultimately a political compromise, a Faustian bargain in Washington that prioritized unnecessary fossil fuel development over local health, water and sovereignty.

Speaker ASenator Joe Manchin's unholy alliance with the Biden administration tipped the scales, shutting down opposition.

Speaker AThe pipeline's approval slipped into a must pass budget deal, short circuited ongoing legal challenges and left many grassroots organizers feeling betrayed.

Speaker AYet as Denali shows in Haller and throughout our conversation, the real legacy of the MVP goes beyond the scar it leaves on the land and highlights the indelible imprint of resistance.

Speaker ANeighbors learning from neighbors, communities forging mutual aid networks and voices long ignored, claiming their part in the bigger narrative of American climate action communities that, as Denali says, became the heartbeat of resistance in Appalachia.

Speaker AIf there is one thing that is clear in our current moment, it is that resistance, resilience and community are the best weapons against the forces that willfully embrace injustice, exploitation and climate destruction in the name of power domination and short sighted profiteering.

Speaker AHaller describes one instance where the initial skirmish was lost.

Speaker AThe Mountain Valley Pipeline was built.

Speaker AUnnecessary, poorly planned and dreadfully executed.

Speaker ABut it was built.

Speaker AAnd methane gas now surges through a pipeline snaking up and down the slopes of Appalachia, across fields and what were once farms.

Speaker ABut the fight is not over.

Speaker AWinds may be few and far between, but the struggle continues.

Speaker AThe bands of resistance remain strong in the face of the proposed expansion of MVP into North Carolina.

Speaker ANo, you didn't want to be David as you sit in the shadow of the Appalachian Mountains sipping your slightly funny tasting coffee.

Speaker ABut unlike the ancient story of David and Goliath, you are not alone.

Speaker AThere are many others everywhere ready to face Goliath.

Speaker ADenali Sai Nalamalapu, author of A Graphic Memoir of Rural Resistance, is one such person.

Speaker AI'll let them take it from here.

Speaker BThanks for your time today and thanks for having me.

Speaker BYeah, and for riding Holler.

Speaker BI think it was a great way to present what happened with the Mountain Valley Pipeline first off, and also the stories of the six individuals and the community and the activism and the despite what happened with mvp, the sense of hope that you conveyed.

Speaker COh, I'm glad.

Speaker BSo tell me about your background.

Speaker BHow did you come to this?

Speaker BHow did you come to write?

Speaker BHaller, what are your thoughts about combining art and storytelling?

Speaker BAnd are you primarily an artist or.

Speaker AA writer or both?

Speaker BHow did you get into graphic novels?

Speaker CSo I grew up in southern Maine and my family's from southern India.

Speaker CSo I grew up with a close connection to two very different environments and also noticing the changes to do with climate change and environmental destruction and the environment.

Speaker CAnd at the same time I from a very young age was very into drawing and writing and I started out drawing cartoons.

Speaker CMy mom gave me a secondhand cartooning book, how to Draw Cartoon Faces, and I spent a lot of time with that as a kid.

Speaker CAnd then as I got older I got into writing as part of school and also it's something I do enjoy and at the same time I was always very connected to the environment and was learning more about climate change, especially when after college I moved to Borneo, an island off the coast of Malaysia and Indonesia.

Speaker CI was in Malaysian territory and I saw what the palm oil industry had done both to the community and to the forest, and decided to go into climate change organizing and carried my skills of writing and art with me as well.

Speaker CAnd then in terms of how this all came together to create Holler, I was seeking a different way to convey the stories involved in the pipeline fight that we hadn't done before that could reach younger audiences and audiences that were too busy to consume.

Speaker CA 300 to 500 page manifesto on climate change and graphic novels came to mind.

Speaker CAnd I think because I'm equally a writer and an artist, the medium suits me very well.

Speaker CBecause I don't necessarily have one medium that I'm more invested in or called to, which maybe would lead to something like a book with some illustrations or a painting with some words or something like that.

Speaker CBut rather I'm very into both of them.

Speaker BI found since I this was my first graphic novel and I'm used to reading those 3 to 500 word manifestos about issues like this was how well it conveyed the stories of the people you highlighted as well as the story of the Mountain Valley pipeline.

Speaker BIt was from my perspective as somebody that is not that familiar with graphic novels, that's how well it conveyed a very complex story.

Speaker BAnd I was pleased.

Speaker BI came away from it going well.

Speaker BThat was easy to digest, but I got the information I needed to get and I come away with a much deeper understanding of the story and especially highlighting the people that are impacted by it and their fight against it.

Speaker BI was impressed with that.

Speaker BI'm still grappling with how you communicate climate change and I think this is a great way to do it, especially as you mentioned, reaching younger audiences, which is very important.

Speaker BYou know, I'm an older guy, I'm a boomer, and I feel a responsibility to somehow communicate what we are leaving to the younger generation.

Speaker BAnd I think this is an important medium and I think you do it very well, actually.

Speaker CI appreciate that.

Speaker CI definitely feel like it's important to have many different ways of communicating the climate crisis.

Speaker CAnd comics and graphic novels have a role to play there.

Speaker CAnd when I started writing this book three years ago, there weren't many climate justice or climate change graphic novels out there.

Speaker CThere's a famous graphic novel by Kate Beaton called Ducks that's more about climate change in the fossil fuel industry and what it's like to be a worker in the industry.

Speaker CAnd then there's an environmental justice graphic novel called Crude that that tells the story of Indigenous communities who are advocating for fossil fuel cleanup that from the mess Chevron left behind in Ecuador.

Speaker CBut I didn't know of many climate justice stories that took place in the US and that were in graphic novel form, especially in Appalachia, which is a region that's been consumed by fossil fuel extraction for more than the past century.

Speaker CSo it felt like an exciting new way to tell the story and something that I could offer to the discourse around climate change that wasn't already there.

Speaker BYeah.

Speaker BAnd I think telling the story of Appalachia is, as you say, has been more or less ground zero for mountaintop removal.

Speaker BThis pipeline that just, you know, the pipeline, it's a disaster, but it's out of sight, out of mind.

Speaker BPeople don't realize what's happening, the impact that has had on people in the region.

Speaker BHow did you find the six people that you highlighted?

Speaker BHow did you find them?

Speaker BAnd what.

Speaker BWhat was your process in deciding which.

Speaker AStories to highlight in the novel?

Speaker CI was already working in the fight to stop the Mountain Valley Pipeline.

Speaker CBefore conceiving of this project, I was working in communications at a grassroots nonprofit to convey to national, local, and regional audiences what the fight was about.

Speaker CAnd so this project came from that work.

Speaker CSo I was already in community with the grassroots movement to stop the Mountain Valley Pipeline.

Speaker CAnd then when I started thinking about whose features, whose stories would I want to be part of this project, I thought of three different aspects of what I hoped the project would be.

Speaker COne is the Mountain Valley Pipeline goes through both West Virginia and Southwest Virginia.

Speaker CTwo different states with different political landscapes, different histories of extraction, generally.

Speaker CAnd a lot of the media coverage of the MVP focused on the Virginia fight, which actually was a smaller portion of the pipeline than the West Virginia side.

Speaker CBut in West Virginia, there's a lot more repression by the state of people's voices and of resistance to fossil fuels.

Speaker CAnd in part because of that, there's more reticence to talk about it.

Speaker CThere's less coverage of these stories.

Speaker CAnd it felt really important to me to have both West Virginia pipeline fighters and Virginia pipeline fighters.

Speaker CSo that's one place I started with.

Speaker CI also wanted to convey the intergenerational nature of the movement because I think a lot of times when people think about activism, they think it's a young person's game.

Speaker CThey imagine, like, young hippies running around the woods or something like that.

Speaker CYeah.

Speaker CBut actually, my experience with MVP fight was that it was very intergenerational.

Speaker CThere was everyone from people in their 80s who were advocating for the stop of the pipeline.

Speaker CMaybe they weren't going to every protest and climbing up every mountain, but they were doing what they could within their abilities to advocate for the end of the pipeline.

Speaker CAnd there was really, there were really young kids.

Speaker CThere were kids who grew up in the resistance, who were infants and children at the beginning, and then who grew up in the 10 years that it took to reach the culmination of this fight.

Speaker CAnd then there were also busy working people, busy single parents, busy parents in the midst of it.

Speaker CAnd I wanted to convey that intergenerational component.

Speaker CAnd then lastly, I wanted to shine a light on what my experience is in terms of the diversity of the region.

Speaker CIt's definitely true that Appalachia is a majority rural, white and elderly region in terms of the scope of the United States.

Speaker CBut as a person of color living in Appalachia, I also know that there are still there are indigenous people living on the land.

Speaker CSo the last chapter of this book features the story of Desiree Shelley, who's a member of the Monacan tribe, whose land is the land I wrote this book on.

Speaker CThere are black communities.

Speaker CCrystal Mello, who is Featured in Chapter 3 of this project, has a mixed race family.

Speaker CAnd that really shaped the way she thought about activism as a white woman.

Speaker CAnd there are immigrant communities.

Speaker CMy parents are immigrants, they didn't immigrate to Appalachia.

Speaker CBut I'm a first generation immigrant and I live in Appalachia.

Speaker CAnd so I wanted to add nuance to the oftentimes oversimplified narratives around the region.

Speaker CSo those were the three sort of buckets that I started with.

Speaker CAnd then from there I thought of different people that I knew and that my community knew along the route and reached out to them and asked if they would be willing to talk to me.

Speaker CAnd then the selection kind of narrowed from there.

Speaker BIn speaking with these more marginalized communities, what does that informed you?

Speaker BHow does, what has that taught you?

Speaker BWhat have you learned from these communities in terms of resilience and resistance?

Speaker BWhat are some lessons that you've learned from how these people that just in their daily lives are up against some form of oppression?

Speaker BHow does that inform your ideas of resilience and resistance?

Speaker COne thing I learned from Appalachians broadly and from people who fought the Mountain Valley Pipeline is that there wasn't any particular party or particular politician that folks could trust or can trust to take care of their lives and well being.

Speaker CThe Mountain Valley Pipeline went through many different stages of going forward and going back.

Speaker CAnd it didn't really matter whether there was A concern, conservative or liberal in power.

Speaker CThere were many people across both parties who were big proponents of the pipeline project and who were infamous for not listening to community and scientists concerns.

Speaker CSo I've definitely learned about the reality of working class people in terms of how politicians treat them and their well being, their future, their demands, everything like that.

Speaker CI've also learned about how important it is to get to know your neighbors because fossil fuel pipelines don't want you to know about the insidious nature of their work.

Speaker CThey don't want you to know that you might lose your drinking water source.

Speaker CThey don't want you to know that the pipeline might explode on a mountainside near you and extinguish your home and your family.

Speaker CThere are many realities of having a pipeline, a massive pipeline project like this next to your home that the pipeline company doesn't want you to know.

Speaker CAnd what I learned through talking to people was that they learned about the realities of this pipeline project by meeting their neighbors and then meeting their neighbors, friends who were scientists or meeting neighbors who knew more information than them and piecing together the puzzle like that, which isn't ideal.

Speaker CIt would be ideal if corporations were held to a higher standard in terms of transparency.

Speaker CBut I did learn a lot about how important it is to get to know your neighbors so that you know what's coming through your community, what's impacting your children's future and so that you can pull your knowledge and fight the bad and fight for the good together.

Speaker BI think that message in climate and, and we're both in the United States so we both know what's going on here.

Speaker BThe sense of community is always critical, but it just seems to be starkly important right now.

Speaker BThere's the Mountain Valley pipeline, but now we're witnessing so much more.

Speaker BLet's just keep it with environment and climate.

Speaker BThe anti science and the corporate takeover of the environment is at a inflection point right now, I think so I think it's very important.

Speaker BThe community is aspect of this is critical.

Speaker BThe book highlights how the community came together.

Speaker BUnfortunately they didn't prevail because of the machinations in Washington I guess, but still it did slow it down.

Speaker BLocal community action is where the resistance happens.

Speaker BAnd I think that you portrayed that in your novel.

Speaker CYeah, I definitely feel that way.

Speaker CAnd I think they're really tangible ways for people to connect to the community around them that are part of Holler.

Speaker CPart of the stories in Holler, like just getting to know the people who live right next door to you.

Speaker CJoining up in local groups so that you can organize together.

Speaker CThere are very specific ways advocating for certain city council candidates who will hold utilities accountable and advocate for climate progress no matter what happens on the federal level.

Speaker CThere are very tangible ways, I think, to connect to your local community and build power together.

Speaker CEven though it can sound like a broad generalization, I feel like people are always saying, build community.

Speaker CCommunity is power.

Speaker BYes.

Speaker CSometimes I imagine for some people, and for me too, it can be like, okay, that sounds nice, but what do I do?

Speaker CAnd to me it's about finding the mutual org or organization, mutual aid organizations near you, meeting your neighbors, finding out who the local political candidates are, who you can ensure hold your, the environmental well being in your community well being as a priority.

Speaker CAll these things are like very specific endeavors that someone who lives anywhere can do.

Speaker CWhether you live in New York City, where we often see big on the streets protests, or you live in Southwest Virginia where you rarely see massive on the streets protests.

Speaker BYou alluded to this before.

Speaker BYou think of activism as a young person's game, but with the pipeline, there were people in their 80s and everybody found their own way to participate, depending on where they're at in life or in the world.

Speaker BIf you don't want to go out and march on the streets, there's other things that you can do.

Speaker BBe involved in your local communities.

Speaker BI remember in the first Trump administration, I spoke with the mayor of Carmel, Indiana, I believe it was, and he was a Republican, but he was also pro climate action.

Speaker BHe was doing what he could in his, as a mayor, in his own community, to simple things like doing roundabouts, just the little things that seem it's not going to make much of a difference, but everybody contributing one aspect of what they can do creates a larger movement toward change.

Speaker BAre you in contact at all still with the folks that you spoke with for the book?

Speaker CYeah.

Speaker CLast night I did a book talk with Michael James Daramo, who is in the fifth chapter of the book.

Speaker CMJD grew up in Blacksburg, Virginia, near Brush Mountain and saw the pipeline come through the forests and the backwoods that they played in as a child and then they were a college student when they found out.

Speaker CSo their resistance was a lot more of what one might imagine as activism like civil disobedience and mutual aid and getting out the vote, that type of thing.

Speaker CAnd then on my book launch, I had a conversation with Desiree Shelley Flores, who is the indigenous seed keeper in the sixth chapter of the book.

Speaker CAnd we got to talk about the work she's doing now and how she's reflecting on the pipeline fight.

Speaker CAnd the coolest thing about being in contact with the six people who are part of this book is reflecting together on the pipeline fight.

Speaker CBecause as you said, it ended in a backroom deal between Senator Joe Manchin, President Biden and other Democratic leaders to greenlight the pipeline through all of the lawsuits and permits that it had lost.

Speaker CAnd now the pipeline's now in service.

Speaker CAnd so now the conversations I'm having with the folks who are part of this book is about how they're reflecting on that ten year long fight.

Speaker CAnd for some, it's more of a reflection on how powerful the community resistance was and how much we learned together about how to build power and how hard this multimillion dollar company had to fight in order to build this pipeline.

Speaker CAnd for others, it's a lot more somber and full of grief, especially for people who for whom the pipeline goes right through their farm.

Speaker CIt's more reflections on everything they lost and how unjust the system is.

Speaker BYeah, that must be just heartbreaking.

Speaker BHow do you feel personally?

Speaker BHow have you dealt with the results of mvp and how do you deal with, you know, when the hopelessness creeps in, which I imagine it must, how do you personally first off feel about the results?

Speaker BHow did you react?

Speaker BHow were your feelings around mvp and just generally with the climate fight, with the activism, how do you maintain your energy and your hope?

Speaker CI remember when I heard that President Manchin had been successful in green lighting the pipeline.

Speaker CIt was a little surreal because he'd been trying to push the pipeline through must pass debt, like debt related legislation for going on a year.

Speaker CAt that point there had been multiple attempts and we had been advocating very strongly to President Biden to stop this unnecessary methane gas pipeline project.

Speaker CAnd so it felt a bit surreal because the Mountain Valley pipeline took 10 years to build, not only because of the powerful community resistance, but because as you said earlier in the program, it was a really poorly done project.

Speaker CIt was a mess of a pipeline project that was planned for the flatlands of the Midwest and then got rerouted into the steep slopes of Appalachia.

Speaker CVery few people ever stepped foot on the land they were going to build this pipeline on.

Speaker CSo there was a lack of understanding of how steep the slopes were, how land side prone they were.

Speaker CThe reality that it's karst terrain, the reality of seismic zones, all of these things.

Speaker CAnd so the pipeline took 10 years in part because they couldn't get the permits they needed to build the pipeline.

Speaker CAnd they Kept getting caught up in legal challenges to do with violating environmental regulations.

Speaker CAnd so hearing that President Biden and the Democrats allowed a pipeline project that was so dangerous and unnecessary to go through in a debt ceiling bill was quite surreal.

Speaker CI remember Senator Tim Kaine of Virginia saying that this is unprecedented that a corporation would have this much power to weasel into a must pass bill in Congress and get greenlit.

Speaker CI also remember there was a lot going on.

Speaker CWe still didn't know if all the legal challenges would just disappear.

Speaker CWe didn't know if all the regulatory agencies would just give them the permits.

Speaker CThis had never been done before.

Speaker CSo it was a long period of a lot of like surprise, confusion, grief, anger.

Speaker CThere were all the emotions.

Speaker CBut I do think in part because the pipeline didn't go through my backyard or my family land, I have the privilege of being part of the climate movement and being part of the pipeline fight for the resistance, for the day to day.

Speaker CI was, I didn't ever join the pipeline fight because I thought there was 100% definite reality that we would win.

Speaker CNothing ever felt 100% possible because of the enormous powers we were fighting against.

Speaker CBut rather because I think what I want to do with this one life that I have on this earth is to be in community with others, to fight for environmental protections that are instrumental to our survival.

Speaker CAnd this was part of it.

Speaker CSo part of how I stay in this work is that I don't depend on hope to continue onto the next day.

Speaker CSometimes I feel hopeful, sometimes I feel hopeless.

Speaker CBut I always feel certain that there is a possibility that we could create a better world that doesn't have these enormous destructive pipelines because it's not written in stone.

Speaker CAnd so for me, fighting projects like this every day and fighting for climate action feels like part of that commitment to the possibility that things aren't this way in the future.

Speaker BYeah, I think that's important to continue to fight the good fight despite the powers arrayed against you.

Speaker BJust the pipeline itself.

Speaker BBut what is the purpose of this pipeline?

Speaker CIt's a boondoggle of a project.

Speaker CThe pipeline was proposed in 2014 during what was called the Appalachian fracking boom, when fossil fuels were fossil fuel.

Speaker CCompanies were just like throwing spaghetti at the wall.

Speaker CThey were like, how many projects can we get done?

Speaker CThey proposed the Atlantic Coast Pipeline, which was a 600 mile pipeline that went through West Virginia, Virginia and into North Carolina and, or no, in West Virginia and Virginia.

Speaker CAnd then they proposed the 300 mile mountain valley Pipeline which went through West Virginia, Virginia and is now trying to expand into North Carolina, and they tried to get as much pushed through as they could, but the reality was that they ended up having to stop the Atlantic coast pipeline and they were able to buy a fluke push through the Mountain Valley pipeline.

Speaker CTheir argument was something along the lines of like, the southeast of the U.S. needs this gas, which it was proven by organizations like the nrdc, the Natural Resource Defense Commission, that this gas was not needed in the southeast of the United States.

Speaker CBecause we know that the United States is one of the most pipeline heavy countries in the world.

Speaker CWe're the biggest fossil fuel villains, in my opinion, in the world, and we produce an insane amount of emissions.

Speaker CAnd we simply did not need another massive pipeline going through the Mountain Valley.

Speaker CMountain Valley pipeline route.

Speaker CBut this company wanted to make money.

Speaker CAnd so their weak sauce argument was that we needed the energy, which wasn't something they were ever able to prove.

Speaker CWe also saw that it didn't bring jobs into the region.

Speaker CInstead of bringing jobs into the region, they hired people from Nebraska and other parts of out west to come in.

Speaker CThey shipped workers, temporary workers in who weren't unionized largely to build the pipeline.

Speaker CAnd then they all left once they were done building the pipeline.

Speaker CAnd also, this is the type of project that costs us money, not only in the near term, but costs people, regular people that aren't the fossil fuel industry money in the long term.

Speaker CBecause climate change is an incredibly expensive crisis to have worsened by projects like this.

Speaker BYeah.

Speaker BAm I correct?

Speaker BIt's bringing tar sands oil from Canada.

Speaker CSo this project is actually methane gas, which is quite a different fight.

Speaker CBecause tar sands oil is so visual for people.

Speaker CYou can see the black liquid seeping into the water, whereas methane gas is invisible.

Speaker CAnd so it is a harder substance for people to conceive of as bad.

Speaker CEven though we know that methane is an incredibly potent greenhouse gas emission that escalates the climate crisis.

Speaker CSo this pipeline happened to be gas, whereas the Dakota Access pipeline and the Keystone XL pipeline were tar sands.

Speaker CYeah.

Speaker BOkay.

Speaker BYeah.

Speaker CAnd line three was also an oil pipeline.

Speaker BAnd wasn't there about a year ago, some explosion or something?

Speaker AYeah, yeah.

Speaker CSo when the pipeline was greenlit, meaning all of the permits that they didn't have were given to them, all of the lawsuits had to be dropped.

Speaker CThey continued to escalate construction at a really alarming speed.

Speaker CAnd there was an explosion when they were testing the pipeline.

Speaker CThey were putting water at a high pressure through the pipeline right by the Blue Ridge Parkway, which is a very beloved parkway that goes through the Blue Ridge Mountains that many tourists come to and many locals love.

Speaker CThere was an explosion of the pipe right there by the Blue Ridge Parkway.

Speaker CIn this instance, it wasn't gas that was exploding out of the pipeline, it was water.

Speaker CBut it was right next to communities that had fought the pipeline for 10 years and was an instance of how alarming and how terrifying it is to live right next to the pipeline when you know that it exploded during testing and now it's in service.

Speaker BYeah, sounds like just a clown car of a construction.

Speaker BWhat is the company behind this?

Speaker BWho is, who's behind?

Speaker CSo this was an interesting aspect of the fight because the Atlantic coast pipeline had big climate villains behind it.

Speaker CDominion and Duke are household names in the region.

Speaker CAnd even outside of the region, people in the US Generally know about the climate villains that are Dominion and Duke.

Speaker CThese are companies that kill people with their power shut offs and that make nonsense, awful decisions to deal with the climate crisis.

Speaker CWhereas the Mountain Valley Pipeline was owned by five different stakeholders who didn't have household names.

Speaker CSo for example, the one of the biggest companies behind the Mountain Valley Pipeline was Equitrans Midstream.

Speaker CNo one, not even I, knew about Equitrans Midstream.

Speaker CAnd I've been in the climate movement since I graduated college for the better half of the last decade.

Speaker CAnd so it did pose a harder challenge communications wise to get people to know about the villains behind this pipeline.

Speaker CBut Equitrans Midstream is a much smaller climate villain that's located in the middle of Pennsylvania.

Speaker CIts headquarters are in the middle of Pennsylvania.

Speaker CAnd if you look into the history behind this company, it's responsible for one of the biggest US climate disasters of 2022, when one of its gas plants was leaking methane gas into the atmosphere for two weeks.

Speaker CAnd this crisis was so bad that people started in the nearby towns to smell the leak, which isn't normal.

Speaker CMethane gas is actually quite a silent killer.

Speaker CAnd then they are also responsible for a house explosion in Pennsylvania that injured an entire family, including a four year old kid.

Speaker CSo when you dig into the company behind this project, you find a very destructive, poorly planned corporation, similar to the climate villains behind other projects, but much less well known.

Speaker BSounds like just hiding behind a huge corporate veil.

Speaker CAnd a lot of these companies have the same funders and some of them are even tied to each other, but they like to break apart to confuse us and make us fight a bunch of different people rather than just the handful of companies that are at the middle of all of this.

Speaker BYeah, I remember when the Compromise was made between Biden and Manchin about this pipeline and they were pushing through, what is it?

Speaker BInflation Reduction act is big climate.

Speaker CIt was a bargain.

Speaker CYeah.

Speaker CHis.

Speaker AYeah.

Speaker BIt's dispiriting to, you know, to pass my climate legislation.

Speaker BI'm going to do this evil.

Speaker BOne step forward, two steps back.

Speaker BSometimes it feels like, yeah.

Speaker BWhat are you doing now?

Speaker BWhat is on your radar as far as activism and resistance?

Speaker CI'm continuing to live in southwest Virginia and continuing to be in community with the people that fought the Mountain Valley Pipeline.

Speaker CAnd I'm also really interested in the power of mutual aid organizations and hyperlocal climate candidates, political candidates at this moment of federal rollbacks against of climate progress.

Speaker CSo I'm very focused on the power of supporting hyper local races like city council, delegate races in Virginia, rural electric cooperatives or utilities.

Speaker CI think all of these races matter a lot in terms of climate action on the local and state level.

Speaker CAnd we've seen that even though Trump has attacked that local climate progress and said that he'll make it impossible, many local candidates, many local politicians are standing up to that.

Speaker CAnd I think that's important.

Speaker CI also think the mutual aid elements of the Mountain Valley pipeline fight were very important.

Speaker CLike, for example, when the tree sits were up in the forest stopping construction from happening.

Speaker CThere were whole networks of people who were feeding the activists, who were making sure that they were supported, who are creating little libraries so that the people in the action camp could read all of these things.

Speaker CI think the ways we keep each other alive are very important.

Speaker CAnd then I'm also, in terms of writing and creating, thinking about, what do you people need right now to support their fights?

Speaker CLike, what can be created in the realm of writing and art to support people in this moment?

Speaker CThat's not just false hope.

Speaker CThat's not just like, it's all going to be okay, just wait for the next administration.

Speaker BRight.

Speaker CThe Mountain Valley Pipeline went through many administrations and there was no one we could wait for on the hyper, like federal, like, bigger level that ultimately would stop it.

Speaker CBut what is the kind of support people are craving when it comes to grounded in reality, climate possibility, stories and pieces of media?

Speaker BAre you working on a book called Not Too Late?

Speaker CSo Not Too Late was a book that I was part of that came out, I believe, in 2022.

Speaker CAnd that was a book edited by Rebecca Solnit and Thelma Lutin Latamboa.

Speaker CAnd that book was a collection of essays and stories about how it's not too late to combat the climate crisis.

Speaker CAnd I wrote a chapter in that book that Fast forwards to 2026, I believe, and tells the story of a child who's talking to their grandmother, who is a climate activist, about how they got to a point of a livable future on this earth.

Speaker BI appreciate the work you're doing.

Speaker BAnd for my listeners, what would you suggest?

Speaker BWhat are some steps they could take to support the frontline movements or tell their own community stories?

Speaker BWhat advice would you give to people that want to do something, might feel overwhelmed, but are motivated right now to do whatever they can to fight all these things that are arrayed against, like you say, a livable, equitable future?

Speaker CThe first thing that I think people should do is meet their neighbors, go to their local city council meetings, talk to local environmental organizations near them, and get to know what are the fights that their community is fighting.

Speaker CFor example, yesterday I did an event in Richmond and we were talking about the multiple Richmond water crises.

Speaker CAnd I think when we get involved in local action, we are able to find ways to expand that beyond our community.

Speaker CAnd so finding ways to be involved in the local struggles that are already happening in your community, whether it's like against something or for a better system, I feel is very important.

Speaker CAnd then also I do think, like telling our own stories of resistance is quite important.

Speaker CWe often feel less let down by mainstream media in terms of what stories they're willing to tell and what perspectives they're willing to uplift.

Speaker CThey often uplift the more like squabbling whatever federal, big federal fights that are happening on the congressional floor more than they'll uplift our stories on the ground.

Speaker CAnd I am very interested in ways that we can share skills within our own community, host skill shares, Write print media to tell the stories, host podcasts, like this podcast we're currently talking on.

Speaker CJust create our own ways of sharing information, I think can also be part of that if there are listeners that are interested in storytelling in particular.

Speaker CAnd I also think for listeners who are wanting to make change within their own home, you mentioned electric cars.

Speaker CThere are many ways that if you have the ability or are phasing out gas infrastructure in your home, there are many ways that we as individuals can lead by example.

Speaker CFor example, this summer, my big project at my house in southwest Virginia is to install solar.

Speaker CAnd my hope is that then my neighbors and my friends will come to my house and they'll see solar and we can have a conversation about it while standing in the yard next to the electric car I already own.

Speaker CSo there's a lot we can do by building relationships with people near us and leading by example.

Speaker BI think those are all good points, excellent points, and I think that's a great way to wrap up our conversation.

Speaker BI appreciate your time and your work and keep doing what you're doing.

Speaker BThis is what we need.

Speaker CThanks so much.

Speaker CIt's been great to talk to you, Thomas.

Speaker BSame here.

Speaker BThank you, Denali.

Speaker CThanks a lot.

Speaker BKeep up the good work.

Speaker CThank you, too.

Speaker COkay, Bye.

Speaker BBye.

Speaker AIn these difficult times of oppression, division and exploitation, I hope this episode inspires you, dear listener, of the power of our collective voices to fight the good fight.

Speaker ARemember, remember that David, in the end, prevailed over the lumbering, impudent Goliath.

Speaker ACheck the show notes for more information about Haller, a graphic memoir of rural resistance and Denali Sai Nalamalapu's work.

Speaker AYou'll also find more information about the Mountain Valley Pipeline and stories of community, resistance and resilience.

Speaker AIf you like what we're doing, please like and subscribe to the podcast.

Speaker AAnd and you can also donate a dollar or two to help keep us going.

Speaker AThanks for listening and we'll see you next time on Global Warming is Real.

Speaker AThere's always more we can do to stop climate change.

Speaker ANo amount of engagement is too little.

Speaker AAnd now more than ever, your involvement matters.

Speaker ATo learn more and do more, visit globalwarmingisreal.com thanks for listening.

Speaker AI'm your host, Tom Schueneman.

Speaker AWe'll see you next time on Global Warming Is Real.